Interview with Preeminent Radiologist Dr. Greg Karnaze, M.D. on Advances in the Field

PhysEmp CEO Bob Truog spoke recently and in depth with Dr. Greg Karnaze, M.D., FACR, about his career in vascular and interventional radiology. Dr. Karnaze is a preeminent physician with 45 years of experience in the medical field. He graduated from Dartmouth College, the University of Kansas School of Medicine, and received his radiology training at the Mayo Clinic where he subsequently was an Assistant Professor at the Mayo Medical School. He is currently a member of Austin Radiological Association a large subspecialty radiology practice in Austin, Texas, that provides imaging & interventional services to 20 hospitals and operates 20 outpatient imaging centers.

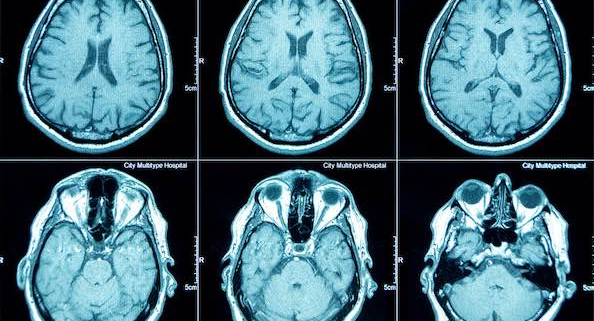

Bob Truog/PHYSEMP: I can’t think of any specialty that’s been more driven by technology than radiology. Tell me about the field’s early days.

Dr. Karnaze: Sure. When I started out in medical school in 1973, the technology was in its infancy. The CT scan was not yet clinically available. By the mid 1970’s there were only CTs of the head. The rest of the body didn’t come along until the late-70s when I was in my residency. There were actually physicians who became famous by publishing papers about the early CT imaging with titles like, “This is the Adrenal Gland” and “This is what a Tumor in the Pancreas Looks Like.”

PHYSEMP: How useful was that in actual practice?

Dr. Karnaze: Until those first images came along, there was no way to really know with certainty what was going on in the body. You had tests that would suggest certain things—blood tests, liver enzymes, and so on. But you didn’t know with real certainty what was happening. Not uncommonly, an exploratory laparotomy was required to visually establish the presence and extent of disease. Now, in modern times, that rarely happens. Now you get a CT or an MRI, and in the majority of cases you know exactly what’s going on.

PHYSEMP: How about ultrasound?

Dr. Karnaze: Back then ultrasound was in a very rudimentary stage. The early machines were these great big affairs hanging on an articulated arm with a probe that could only do a single plane of imaging as it moved along. You had to put the images together like lines on a TV and try to come up with a useful composite image in your mind. Then there were advances, and a transducer that generated an image in real time was developed. You could see exactly what you were looking at, as opposed to just gathering data and translating it into images later.

PHYSEMP: How did this evolving technology affect the way that patients are treated?

Dr. Karnaze: A lot of conditions had been treated surgically that didn’t need to be anymore. For example, if you had someone with acute appendicitis, they were operated on and the appendix was taken out; but then it ruptured, and a week later developed an abscess. That would require another operation. With CT, that almost never happens. We use scans to guide us: we put the needle in and using a guide wire we dilate the track and then slide a drainage tube in through the skin and take care of the problem that way. It stays in for a week and that’s generally the end of it. Also, the number of operations for appendicitis that aren’t really appendicitis has decreased dramatically because we can image the appendix. If appendicitis is suspected, we can make the correct diagnosis (appendicitis or no appendicitis) more than 90% of the time.

PHYSEMP: Has imaging impacted traditional kinds of diagnoses like physical exams?

Dr. Karnaze: In truth, while there have been a lot of advances in the field of medicine, there’s also been a degree atrophy of certain diagnostic skills. One of these is physical diagnosis—using the hands to feel for a problem, such as, for example, an enlarged liver or spleen. There were always certain physicians who were masters at diagnosing by examining the patient. That whole skillset has largely been supplanted by imaging and sophisticated laboratory tests.

PHYSEMP: A friend of mine, an internist trained in Europe, said something like that when she came to the U.S. to practice. In Europe, she said, “We don’t have the technology that you have. We put our hands on people.” When residents came through on her rotation, she required that they touch the patients.

Dr. Karnaze: There can be a synergy between the two approaches—the hands-on and the technological. It’s unfortunate that internal and primary care medicine have become so totally reliant on imaging and laboratory tests to the exclusion of human touch.

PHYSEMP: Let’s talk for a bit about the process of bringing young physicians onboard at your practice. Given that you’re the head of a large group, do you get involved? Do you interview them?

Dr. Karnaze: By the time a physician comes in for an actual interview, we’ve already done a lot to see if they will be a fit for the practice. They generally come in with recommendations. And they’ve gone to a good program, which is always a plus.

PHYSEMP: Once they hit those marks, what are the make-or-break qualities that you look for?

Dr. Karnaze: Very importantly, we want to make sure that they’re somebody we’ll get along with. And that they are someone who’s going to be committed to the practice, who’s going to come and stay with us.

PHYSEMP: How are recent residents’ adjusting, coming right out of school?

Dr. Karnaze: They don’t have an authority figure around anymore to guide them and tell them what to do. When you’re a resident, there’s always somebody to check on you. In private practice, it becomes peer-to-peer support. And in transitioning from being a resident into private practice, you have many decisions to make. Hundreds of decisions every day. We look for young doctors who can do that.

PHYSEMP: You can’t be running down the hall asking colleagues, “Hey, is this right?”

Dr. Karnaze: We get paid for the work we do; not directly for how smart we are or how we performed in school. Everything is based upon quality production of work. Whether that’s seeing patients as an internist or interpreting examinations as a radiologist, or doing operations as a surgeon, it’s about being as productive as you can while providing the best care possible.

PHYSEMP: You’re a part of the largest radiology group in the world—something like 3,000 radiologists? The typical size of a radiology group is probably around 11 or 12. What’s that like?

Dr. Karnaze: The advantage of being in a large group is that we can afford to invest a lot in IT and infrastructure. We deploy a large PACS [Picture Archiving and Communication System]. We provide digital imaging services to all of our 20 outpatient imaging centers, to all the Ascension hospitals in Austin, and now to all of the HC hospitals, too (all their imaging is done through our PACS system). It’s a very unique thing to the city because if, for example, a patient shows up at hospital X that’s not in the same network as hospital Y, or at one of our imaging centers, when that patient comes in and you bring up their scan, you have a list of all the studies they’ve had done in the entire city at all the hospitals and all major medical practices.

PHYSEMP: What an advantage to patient care that must be. Where do you see your career going from here?

Dr. Karnaze: I’ve been doing this for a long time and I still enjoy it. My group ARA which is part of Radiology Partners (the largest radiology group in the country with 3,000 radiologists) has many exciting things in the pipeline. We are starting a radiology residency in association with the University of Texas Dell Medical School with the first group of residents arriving this July.

Because of the size and resources available to Radiology Partners we are involved in several projects utilizing Artificial Intelligence. One of these assists us in making evidence-based best practice recommendations for further evaluation and treatment of findings on imaging studies. This is very helpful for most of our referring physicians who may not be familiar with every most appropriate next step when there is an unfamiliar finding on an imaging study. This helps reduce unnecessary additional testing while at the same time facilitating appropriate additional evaluation when appropriate.

Another AI project is being done in conjunction with a 3rd-party company to help patients and referring physicians ensure that appropriate follow-up is actually performed on significant findings so that important findings don’t fall through the cracks and result in poor patient outcomes.

Our Molecular Imaging subspecialists have started operations of one of very few private practice theranostics programs in the country. The concept of theranostics is the combination of both therapeutics and diagnostics in one package for image-guided therapy and also for defining the treatment outcome at an early stage of various cancers. The era of theranostics offers a great opportunity to improve patient care, and it’s clear that theranostics will become a mainstay of personalized cancer treatment.

The pace of advancement in diagnostic, therapeutic, and imaging guided interventional procedures continues to advance. Diagnostic Imaging and intervention remain exciting areas to work in and are essential in the modern health care system.

PHYSEMP: Thank you for your time. Those sound like incredible advances.

Dr. Karnaze: Thank you as well. It’s been a pleasure.